Mary as Virgin and Whore:

Restoring Wholeness to the Image of the Feminine in Christianity

Cynthia Avens

The DaVinci Code, the suspenseful thriller written by Dan Brown that was #1 on the New York Times Bestseller List for many weeks, has recently introduced thousands to the ancient but little known mysteries surrounding the Biblical figure of Mary Magdalene. The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, discovered in 1896 but known only to the few scholars who studied such ancient texts, has been hailed as "the appropriate gospel to inaugurate the third millennium." (1) The December 8, 2003 issue of Newsweek magazine carried an article titled "Mary Magdalene: Decoding the DaVinci Code." These are just a few of the recent signs that the divine Feminine is emerging powerfully today in the figure of Mary Magdalene - not the "spiritualized" Virgin Mother of Christ - but the more complete and complex figure of Mary that integrates sexuality and spirituality. The divine Feminine that has been hidden within Christianity has been very well disguised in the personage of Mary Magdalene. The Feminine that has been reviled and persecuted by the patriarchal traditions of Christianity can be seen in Mary Magdalene, whose role as the spiritual initiate and consort of Christ was perverted into that of the repentant whore. But the hidden and persecuted divine Feminine is now making herself known in all of her guises - not only as the compassionate mother, but also as the spiritually powerful and wise consort.

The divine Feminine, known in the Judeo-Christian tradition as Sophia, is claiming her place once again in the consciousness of humanity. And in the possibility that we may finally be open to receiving her wisdom lays the hope for our future.

In ancient cultures the Divine typically manifested in the polarity of a god and goddess, united in the divine syzygy that integrated both masculine and feminine elements. The Great Goddess and her Son/Lover can be seen in figures that span an immense variety of ages and cultures, such as Isis and Osiris, Ishtar and Tammuz, Inanna and Dumuzi, Asherah and Baal, Cybele and Attis, and Aphrodite and Adonis. The two aspects of the feminine function, the "static" or mother goddess, and "transformative" or goddess of love,(2) are united in the archetypal Great Goddess. But in both of her roles, as mother and beloved, the essence of the Feminine is directly related to sexuality. Feminine power is expressed through fruitfulness that is rooted in the instincts - in birth-giving, the seasonal cycles of Nature, and intimate relationship. Although this figure of the Great Goddess was harshly suppressed by the Christian Church, as an archetypal essence she can never be completely destroyed. She has re-emerged in various guises throughout Christian history, but particularly in the figure of Mary. However, the symbol of "Mary" as representative of the divine Feminine in Christianity was split asunder into two opposing images: the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene.

The ancient symbolism of the Great Goddess and her Son/Lover is hidden in this duality, for Jesus Christ is the son of the Virgin Mary and the beloved of Mary Magdalene. The urgent need today is to restore wholeness to this archetypal image of the divine Feminine that has manifested in Christianity and which therefore has profound significance for Western culture. This task will be accomplished particularly through re-imaging the role of Mary Magdalene and restoring her to the position of power that she held in the early Christian community.

The figure of Mary that has been dominant in Christian history, the "Blessed Virgin" and "Mother of God,"

expresses one pole of the archetypal energies of the Goddess. The story of how the humble, obedient young woman depicted in the gospel accounts of Jesus' nativity was transformed into the "Queen of Heaven" (a title given previously to the ancient Goddess) is in itself a fascinating exploration of an evolving mythology within Christianity. Christian theologians have emphasized that Mary herself is not divine - only her Son is God - yet dogmas established by the Church throughout the centuries have had the effect of divinizing her status. The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, which states that Mary's own conception was sinless or "immaculate," and the dogma of the Assumption of the Virgin, which claims that Mary was assumed bodily into Heaven, serve to remove her from the earthly human world and place her within the realm of the divine. But the Virgin Mary as presented in Christian tradition is a greatly diminished embodiment of the figure of the Great Goddess. As the "second Eve," Mary overcomes the sin of the original Eve of Genesis, which came to be interpreted by the fathers of the Church as sex. Thus, the figure of the humble, pure, ever-Virgin Mary completely reversed the role of the powerful, sensual, fertile Great Goddess. The primary figure of the divine Feminine in Christianity was now sexless.(3) This image of the Feminine was never an easy one for women to use as a model in their ordinary lives, and is especially anachronistic in our modern world as women increasingly claim their power in all areas of their lives, including sexuality.

In contrast to the dominant role of the Virgin Mary in Christianity, Mary Magdalene presents a much more mysterious and ambivalent figure.

Very little is actually known about her. Yet there are powerful clues in the canonical Gospels that clearly demonstrate the importance of Mary Magdalene's role in the early Christian community. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John all make reference to her as one of the women followers of Jesus. In the Gospel of Luke she is included among the "women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out." (Luke 8:2) The healing of Mary Magdalene by casting out her "seven demons," probably what we today would label a mental illness such as dissociative disorder or schizophrenia, was very likely the initial experience that prompted her to follow Jesus. Another pertinent fact in this passage is that the appellation "Mary, called Magdalene," referring to her birthplace rather than her role as someone's wife, mother, or daughter, indicates that she has a unique, independent status among the female followers of Jesus.

Mary Magdalene's primary significance in the canonical Gospels, however, relates to the role that she plays during the events of Christ's crucifixion and resurrection. She is explicitly mentioned as one of the women present at Christ's crucifixion, a demonstration of feminine courage fueled by love, as most of the male disciples had fled the scene in fear. In all of the Gospel stories it is she, sometimes accompanied by other women, who goes to the tomb of Christ on "the third day." In some accounts she carries spices to anoint his body. This is the image the early Christians had of her - as one of the myrrhophores, or ointment bearers.(4) Her love of Jesus and continued faithfulness to him endures beyond his bodily death and the agonizing doubts following his Crucifixion. It is the power of her love and the purity of her faith that enables her to witness his Resurrection. The beautiful passage in the Gospel of John that so movingly describes Mary's experience at the tomb is familiar to all Christians:

Jesus said to her, "Why are you weeping? Whom do you seek?" Supposing him to be the gardener, she said to him,

"Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him,and I will take him away. Jesus said to her, "Mary."

She turned and said to him in Hebrew, "Rabboni!" (John 20:15-16)

After hearing Jesus' message to her regarding his Ascension, "Mary Magdalene went and said to the disciples, 'I have seen the Lord'; and she told them that he had said these things to her." (John 20:18) Thus, it is Mary Magdalene who has the privilege of being the first to see the resurrected Christ. As the first to bear witness to the Resurrection, she carries the essential message that has formed the central tenet of the Christian faith. This certainly gives her pre-eminence among all of the followers of Jesus, a fact duly noted by the Church in its appellation of Mary Magdalene as "Apostle to the Apostles."(5)

The only direct references to Mary Magdalene in the canonical Gospels are these events: the casting out of seven demons, witnessing the Resurrection, and informing the other disciples of this miracle. How, then, did this woman who is portrayed in the Gospels as the most faithful and the most esteemed of all of Jesus' followers come to be recast in the role for which she is best known, that of the penitent whore? This designation officially dates from the 6th Century, in a homily delivered by Pope Gregory I ("the Great"), in which he conflated Mary Magdalene with the unnamed "sinful woman" in the gospel of Luke who anointed the feet of Jesus with oil from her alabaster jar and wiped them with her hair. Gregory interpreted the sins of this woman - never mentioned in the Gospel account - as prostitution, and claimed that she was the same person as Mary Magdalene, whose seven demons also signified her sin. From this time on, the primary symbols for Mary Magdalene became the alabaster jar and her luxurious hair, and her chief designation as the "penitent whore." This was the case even though there is no Biblical evidence to support the view that the sins of the woman who washed Jesus' feet were sexual in nature, nor that this "sinful woman" was in fact Mary Magdalene! It was not until 1969 that the Roman Catholic Church officially removed the label of the redeemed prostitute from Mary Magdalene, but all of the images through the centuries that depict her as the erotic figure with long tresses are impossible to erase. Thus to this day it is still the figure of Mary Magdalene as the repentant prostitute that dominates the popular imagination.

This denigration of the character of Mary Magdalene certainly appears to be the result of the patriarchal bias of the Church Fathers in their successful attempt to devalue the Feminine and its association with sinful sexuality. Mary Magdalene was held up as a model of repentance for others to follow, as she had overcome the evil powers of sex and received forgiveness for her sins. Thus, Mary Magdalene also took on the role of "the second Eve" as a counterpoint to the figure of the innately chaste Virgin Mary.(6) But there is a deeper mystery surrounding the sexual nature of Mary Magdalene than simply the attempt by the patriarchal Church to devalue the most powerful woman of the early Christian community. The aura of sexuality that clung to Mary Magdalene in early legendary accounts is reminiscent of the sexual powers of the ancient goddesses. Even her designation as prostitute symbolically associates her with the "sacred harlots," the temple priestesses who served the Goddess through the gifts of their sexuality. The litany of the Great Goddess as Lover resonated throughout the apocryphal legends concerning Mary Magdalene. It is perhaps because of the persistence of these sexual overtones associated with her that the Church Fathers cast her in the role of redeemed sinner.

The Mother aspect of the Great Goddess could be accepted as long as the sexual basis for motherhood was denied, as in the case of the Virgin Mary. But the Great Goddess in her role as Lover was anathema to the Fathers of the Church; therefore, Mary Magdalene as the symbolic carrier of this archetype had to be stigmatized, and her sexual energy repressed through her "redemption."

It is in her role as the Beloved of Jesus that Mary Magdalene's association with the Great Goddess as Lover is most clearly seen. The spiritual intimacy between Mary Magdalene and Jesus can be easily documented, but whether or not they were physically intimate is a matter that at this time must be left open to conjecture. However, the intimate relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene is one of the deepest mysteries within Christian spirituality, and is most certainly the reason for the outpouring of interest in the figure of the Magdalene in our own day. Even the traditions of the Church recognize the mystical importance of their relationship. In the 3rd Century, Hippolytus made a connection between Mary seeking Christ in the garden and the Bride in the "Canticle of Canticles" who is seeking the Bridegroom. From this time on, Mary Magdalene acquired the title of "Bride of Christ."(7) As Mary Magdalene weeps in the garden before seeing her resurrected Lord, she enacts the role of the archetypal grieving goddess that is searching for her slain lover/god. Within Christian tradition, the drama of Mary's sorrow for the crucified Jesus follows a pattern similar to that of the other ancient Mystery Religions. Hers is the same image as Isis weeping over the dismembered body of Osiris, Aphrodite mourning the slain Adonis, and Inanna lamenting for the dead Dumuzi. The myth of the Goddess searching for her Son/Lover who has died a sacrificial death and been reborn was found throughout the ancient world.(8)

It is in the Gnostic scriptures, however, rather than the canonical Gospels that we find the clearest portrayal of Mary Magdalene as the beloved of Jesus. Gnostic texts, denounced by the Christian Church as heresy, were for the most part literally buried until the momentous discovery at Nag Hammadi, Egypt in 1945 that uncovered these alternate scriptures. One of these texts, "The Gospel of Philip," gives a much more specific and detailed description of the intimacy between Jesus and Mary Magdalene than that which was recorded in the texts accepted by the Church. "The Gospel of Philip" reports that Jesus "loved her more than all the disciples and used to kiss her often."(9) This gospel refers to Mary Magdalene as "the one who was called his companion."(10) The meaning of the Greek term for "companion" that appears in this passage is understood to be consort or sexual partner.(11) It is, however, important to guard against the mere literalizing of the intimate relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene, and to examine more deeply the underlying meaning which is symbolized by this partnership. In many of the Gnostic scriptures Mary Magdalene appears as a representative of the divine Sophia, the goddess figure of Wisdom within Jewish and Christian tradition. The relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene in the earthly world mirrors the marriage of the Logos and Sophia in the heavenly realm.(12) Mary Magdalene as the human consort of Jesus is a symbolic image of Holy Sophia as the spiritual consort of Christ. Thus it is through Jesus and Mary Magdalene that the deep mystery of the "hieros gamos,"or sacred marriage, continues in Christian tradition. The archetypal union of the masculine and feminine, as seen in the god and goddess of the ancient Mystery Religions, is deeply hidden within Christianity in the mysteries of the Magdalene.

The Gnostic texts also portray Mary Magdalene as the inner initiate of Christ, the only disciple who truly understands the deeper spiritual truths embedded in his teaching. She is both the "illuminator," or "enlightened one," and the "illuminatrix," or "light-giver."(13) "The Dialogue of the Savior" refers to her as "a women who understood completely,"(14) also linking her with Sophia as Wisdom. She is the liminal woman, the mediatrix of the realms of the unconscious, of visions, and death. She exemplifies the true gnostic, who follows the path of inner spiritual knowing rather than the doctrines of organized religion. This inner way of knowing was always feared by the Church hierarchy as a possible threat to their authority, so this is another reason that Mary Magdalene's role as a woman of wisdom was perverted by the Church. The depth of her character and profundity of her spiritual insights are much more developed in the Gnostic texts, especially in the one that bears her name - "The Gospel of Mary Magdalene." In this gospel she relates the mystical wisdom that she received from the risen Christ through a visionary experience. In response to Peter's criticism of her teaching, Levi replies, "If the Savior made her worthy, who are you indeed to reject her? Surely the Savior knows her very well. That is why he loved her more than us."(15) Here again Mary Magdalene is endowed with qualities of the divine Feminine, as the goddess of wisdom and the beloved of the god.

The negative reactions of the apostle Peter to Mary Magdalene that are recorded in a number of the Gnostic texts are a reflection of the Christian Church's attitudes toward women in general and Mary Magdalene in particular. Peter, as the "Rock" upon which the Church was built, represents the institution that developed a dualistic view of the physical and spiritual worlds. In this perspective, the material world - including the body and its instincts - was seen as evil, and must be denied in order to reach the pure realms of spirit. The Feminine, in her association with the physical world, was devalued, and women's roles in the Church were harshly proscribed. Female Christians no longer had the equal roles that they did in the earliest Christian communities. As a corollary to the denigration of women that escalated as the Church developed its institutional structure, Mary Magdalene's role as the consort of Jesus, the leader among the disciples, and the most spiritually enlightened of his followers, also virtually disappeared from the annals of Christian history, to be replaced by the dominant image of her as a penitent whore. Today it is imperative to restore the original understanding of Mary Magdalene's role within the Christian community and to elevate her once again to her position of prominence as the "Apostle to the Apostles" and the "Bride of Christ." Then women can truly follow Mary Magdalene as a model in cultivating their own feminine spiritual vision and participating equally with men in all areas of life.

An even more profound task that challenges us today is to restore wholeness to the image of the divine Feminine that was torn asunder by Christianity's splitting the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene into polar opposites. The two Marys must be reunited so that the archetypal energy of the Great Goddess can once again flow into our lives and revitalize our culture. Central to this task is the acknowledgement of the instinctual nature as the sacred essence of the Feminine, and the cultivation of a spirituality that encompasses sexuality. Integration of the archetypal Feminine as mother and lover must be accomplished both personally and mythologically. As individual women we must commit ourselves to the inner work required to become consciously whole. In this way we can mediate the power of the divine Feminine by expressing the full range of her creative energies, through motherhood, artistic creation, spiritual vision, intimate relationships, and sexual passion. Our personal inner work must be accompanied by the development of a corresponding mythological image of divine Feminine wholeness. Sophia, the Goddess of Wisdom hidden within Judeo-Christian tradition, provides us with an accessible and appropriate symbol for restoring unity to the image of the divine Feminine in Christianity. The Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene represent the two aspects of Sophia depicted in the Gnostic scriptures. The Virgin corresponds to the "higher Sophia" that exists in the archetypal realm of the Pleroma; the Magdalene reflects the "fallen Sophia" that has been cast into the material world and is rescued by her lover, the Christ. That the two Marys share the same name points to the fact that they symbolize two complementary aspects of the same archetype.(16) Mary as Virgin and the Magdalene can be mythologically integrated in Christian spirituality by recognizing their unity in the figure of divine Sophia.

The restoration of wholeness to the image of the Feminine allows for completion of both the masculine and feminine and their ultimate union. As the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene unite in the figure of Sophia with Christ as her Son/Lover, the profound mystery of the divine syzygy will again be revealed. The "hieros gamos," the sacred marriage that unites masculine and feminine, symbolizes the union of the ego and the Higher Self, or the union of the soul and God. The sacred marriage within the self leads to psychological integration and spiritual enlightenment, and is the basis for the fulfilling partnership of two whole individuals who can embrace all aspects of life and celebrate the sacredness of sexuality and the sanctity of love. It is the "hieros gamos," dependent upon a holistic image of the Feminine, that is necessary for the spiritual evolution of humanity.

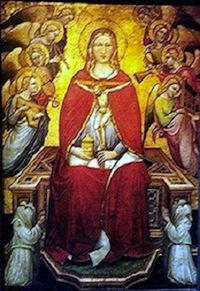

The energies of the divine Feminine are pouring forth today from the dark, hidden places where she has been buried throughout the centuries. We are now in a position to provide channels for her archetypal energies in the form of our cultural symbols by consciously re-imaging them in such a way that they give truthful and complete expression to the divine Feminine. This is the message that Mary Magdalene brings to us today: the divine Feminine is returning in a form that is in full partnership with the Masculine. Within Christian tradition, this is beautifully symbolized in artistic images of the "Coronation of the Virgin." The "Queen of Heaven" who wears the crown, the Christian expression of the Great Goddess, is Mary as both the Mother and the Beloved. The representation of Christ and Mary, God and Goddess reigning together in Heaven, is truly the image for the third millennium of Christianity.

For more information refer to Walking the Path of ChristoSophia: Exploring the Hidden Tradition in Christian Spirituality Chapter IV "Gnostic Christianity"

NOTES

1. Jean-Yves LeLoup, The Gospel of Mary Magdalene (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2002), p. 175.

2. Nancy Qualls-Corbett, The Sacred Prostitute (Toronto: Inner City Books, 1988), p. 57.

3. Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), p. 141.

4. Ibid., p. 62.

5. Ibid., p. 65.

6. Ibid., p. 141.

7. Ibid., p. 63.

8. Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (London: Arkana, 1993), p. 221.

9. James M. Robinson, Ed., The Nag Hammadi Library (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1988), "The Gospel of Philip," p. 148.

10. Ibid., p. 145.

11. Haskins, p. 40.

12. LeLoup, p. 110.

13. Haskins, p. 226.

14. Robinson, "The Dialogue of the Savior," p. 252.

15. Robinson, "The Gospel of Mary," p. 527.

Back to top