.

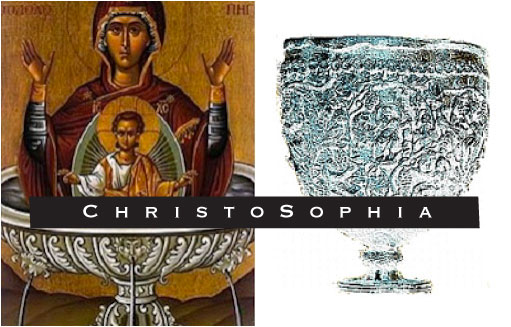

The Grail of ChristoSophia

The Holy Grail, as a symbol which connects the ancient wisdom of the pagan past and the mysteries of Christianity, is a key to the new mythos which is emerging in our culture. In our current age, when many people no longer find spiritual vitality within the traditional symbols of Christianity, it is especially important to turn to the Grail for the numinous power which it retains. Historically the Grail has occupied a paradoxical position within Christianity, for although the Christian church never embraced the Grail in its formal doctrines, nevertheless this symbol has played a very significant role in the esoteric traditions of Christianity. As Carl Jung has pointed out, the orthodox Christian concept of deity in its Trinitarian form does not provide an image of wholeness because it excludes the feminine and the dark side of God.(1)

However, we now find ourselves in a time when our cultural myths and symbols are undergoing major transformation. It is the Grail which can provide the much needed symbol for a revitalized Christian mythos for it integrates the feminine aspect of God with the masculine, thereby including nature and the dark side of existence in its image of the Divine.

The source of Christian versions of the Grail motif is found in earlier pagan Celtic mythology, which emphasizes the feminine aspect of the Grail. A primary image of the Grail in Celtic mythology is the magical cauldron of the Goddess. The cauldron is a deeply feminine image because all that it provides - nourishment, rebirth, intuition and wisdom - are functions of the feminine. The guardians of the Grail in its form of cauldron or cup are also feminine in Celtic mythology, representing the Goddess of the Land who is called Sovereignty. She is often depicted in her role as the Black Goddess, and the quest of the Celtic hero results in marriage to her. This represents the Sacred Marriage, the union of the King and the Land as Sovereignty, and the integration of the masculine and the feminine which results in the fruitfulness of body and soul.(2)

The tragedy which results from the disruption of this sacred union is recounted in "The Elucidation," a medieval tale which has particular significance for our modern day. The Realm of Logres (Britain) is depicted originally as a paradise in which the inner and outer worlds are in harmony. Sacred wells and springs in the land are attended by maidens who offer a golden cup to all travelers which provides whatever food and drink is desired. The golden cup is a form of the Grail as a limitless source of sustenance, which parallels the plenitude of nature to be found in this paradisal world. This condition of blessed abundance is disrupted, however, when the evil King Amangons rapes one of the well maidens and steals her golden cup. The result of this abuse of patriarchal power is that the maidens of the wells, guardians of the Grail, go into hiding and are seen no more. The loss of the "voices of the wells"(3) causes the Realm of Logres to become a barren wasteland where the waters dry up and all growth withers. The quest of the Grail hero is to seek the Court of Joy so that the waters will flow freely and the Earth will be made green again. It appears that this can only be accomplished by re-establishing the union between the King and the Goddess of the Land.

We find ourselves today in the land which has lost the maidens of the wells. When the golden cup of the Grail was stolen, the experience of wholeness was lost. The rape of the well maidens caused a disruption of the harmony between the masculine and feminine, and consequently between the outer and the inner worlds. This theme reflects the development of patriarchal consciousness in Western culture which is mirrored in the rise of organized Christianity. The suppression of the feminine voice in Western culture parallels the loss of the feminine dimension of the Divine in the orthodox Christian concept of God.

During the Middle Ages there was a brief reappearance of the feminine as the "voices of the wells" were heard in the love songs of the troubadours and in the Grail tales of the poets. Because of the predominance of the Christian church in society at this time, many of the legends of the Grail which were written in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries were strongly influenced by Christianity. However, much of this influence actually came from the traditions of Celtic Christianity through which percolated the earlier pagan Celtic images of the Grail, and Gnostic Christianity with its feminine representations of the Divine. As Emma Jung suggests, the rapid development of the Grail mythology during the Middle Ages and its immense popularity was due to the psychological need "to complete the Christ-image by the addition of features which had not been taken sufficiently into account by ecclesiastical tradition."(4) Thus the symbol of the Grail as it reappeared to the Christian populace of the West in the Middle Ages was an attempt by the psyche to integrate the polarities of good and evil, masculine and feminine, spirit and nature which had been split apart in institutional Christianity. Under the influence of Christianity the Grail as Celtic cauldron was transformed into the cup which was used by Christ at the Last Supper and subsequently the chalice of the Eucharist. This new image of the Grail as a relic of Christ's blood appeared for the first time in the story "Joseph of Arimathea" which was part of the "Roman de L'Estoire dou Graal" trilogy attributed to the Burgundian poet Robert de Boron. (5)

This tale begins with the story told in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. After the crucifixion, Joseph of Arimathea goes to Pontius Pilate and obtains Christ's body and the cup which he had used during the Last Supper. While preparing Christ's body for burial in his own tomb, Joseph catches the blood which flows from the wounds into the cup and takes it to his home. When the Jewish authorities discover that Christ's body has disappeared, they throw Joseph into prison. In de Boron's version, Christ appears to him while he is imprisoned and brings him the cup, informing him that he is to be its guardian and instructing him in the symbolism of the mass. Joseph remains there for forty-two years, during which time he is sustained physically and spiritually by the Grail. After his release the holy relic which contains the blood of Christ is brought to Britain, where it remains hidden to this day.

Thus the representation of the Grail as the vessel of the Goddess was transformed into the primary Christian image of the Grail as the chalice containing the redemptive blood of Christ. The same symbolism is seen in Robert de Boron's "Joseph of Arimathea" as in the Celtic stories of death and rebirth from the cauldron of the Mother Goddess. Her Grail symbolizes both the womb and the tomb, for it is she who initiates the cycles of life, death, and rebirth. The Grail of Christ possesses a similar meaning, for it contains the blood which flowed from his wounds and thus represents his death on the cross. But the chalice which contains the sacrificial blood of Christ becomes the womb which gives new life to the faithful during the ritual of the Eucharist. The central sacrament of Christianity is based on this mystery of the Grail. From ancient times blood as the principle of life has been thought to possess magical qualities. It has often been identified with the soul, the essence of life. Thus the Eucharistic chalice which contains the blood of Christ has such numinous power because it in effect holds within it the "soul-substance" of Christ, the essence through which he mystically continues to live.(6) The Christian who drinks from this chalice partakes of the essence of Christ and is therefore able to participate in the resurrected life. The meaning of the Grail of Christ as a vessel for salvation, however, lies much deeper than simply physical immortality. For ultimately the Grail is a "vessel of spiritual transformation." (7) Drinking from the chalice of Christ's blood in the Eucharistic ritual brings about a spiritual renewal that has its analogue in the knights who succeed in their quest for the Grail.

The similarity of imagery associated with Christ and the pagan Celtic Goddess demonstrates that the feminine aspects of the Divine which were suppressed in the mainstream Christian church emerged through the symbolism of the Grail. However, within Christianity itself there is a figure of the Divine Feminine which was lost to the church when the feminine voices of the wells were silenced. Her name is Sophia; she is the personification of divine Wisdom. A major task of the Grail seeker today who quests for the Grail of Christ is to bring Sophia forth from her hiding places within Christian tradition.

This quest must begin within Judaism, for this is where the roots of the Christian concept of deity are found. The role of Sophia is seen most clearly in the Wisdom literature of the Hebrew Bible and the Apocrypha, where she is variously recognized as the first creation of God, as co-creator and mediator between God and the world, and as the emanation of divine joy and goodness throughout all creation.

This Sophianic theme was understood and further developed by those Jews who became Christians in the first centuries following Christ's resurrection. The concept of the Word (Logos) linked with Wisdom (Sophia) was a tradition in the Wisdom theology of Judaism prior to the birth of Jesus. The earliest Christians were profoundly influenced by the concept of the Logos held by their contemporaries, the Hellenistic Jews, as they sought to explain the person and purpose of Jesus Christ. Thus the Christology of the early Christians was based on the belief in Jesus Christ as Logos incarnate ("the Word made flesh"), to whom the attributes of Sophia were transferred.(8)

During the first few centuries of Christianity Jesus Christ was actually viewed as the incarnation of Sophia. The early Christian missionary movement preached the gospel of the resurrected Christ as the life-renewing Sophia-Spirit. As Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza says, "The proclamation of Jesus Christ as the Sophia of God and the cosmic Lord functions in the Christian community as the foundational myth."(9) However as the role of Sophia became increasingly submerged in the figure of Christ during subsequent centuries, the Sophianic nature of Christ truly became a hidden secret to most Christians.

It has been primarily the Christian mystics, traveling their solitary paths through uncharted terrain in the same manner as the Grail seekers, who have discovered the hidden presence of Sophia in their inward journeys. One of these great spiritual seekers was the German shoemaker Jacob Boehme (1575-1624), who describes Sophia as a majestic figure of power and glory in a manner similar to the Jewish Wisdom literature. Through his visionary experiences he discovers Sophia's secret hiding place within Christ. His statement, "the noble Sophia hides herself in Christ's fountain"(10) expresses his mystical understanding of the association of Christ with the Goddess and the Grail. Boehme's statement that Sophia "has revealed Herself in the precious name JESUS as Christ"(11) expresses the same understanding of the Sophianic nature of Christ that was held by many in the earliest Christian communities. Boehme also recognizes the central importance of the Divine Feminine to the entire Trinity for he says, "She is the seeing as Holy Spirit, the mirror as Son and the eye as Father."(12)

This recognition of Sophia within the nature of the Godhead itself is echoed in our modern era by some Russian mystics such as Vladimir Solovyev and Sergei Bulgakov. Solovyev (1853-1900) was a philosopher-poet whose mystical experiences with Sophia inspired the philosophical and religious tradition called Sophiology in modern Russia. Solovyev describes Sophia as the "substance" of the Trinity, "the divine principle of all-in-oneness, which is the Wisdom of God."(13) Sergei Bulgakov (1871-1944), a Russian Orthodox priest whose own conversion to Christianity occurred as a result of his mystical encounter with Sophia, also viewed Sophia as the "ousia" or substance of the Godhead. He describes Sophia as "the nature of God...a living...loving substance, ground, and principle."(14) The Russian Sophiologists' view of Sophia corresponds to that of the Jewish Wisdom literature in their understanding of her role as both the creative power of the Divine and the emanation of God throughout all of creation. This understanding of Sophia's dual nature was described by Solovyev as the heavenly figure of Wisdom and the "World-Soul" which is the divine presence within creation. The mystics' understanding of the paradoxical unity of these two attributes of Sophia is the basis for recognizing the Divine as transcendent and at the same time immanent within nature.

The Grail questor today who follows the pathways of the Christian mystics will find that Sophia is hidden in the chalice of Christ, just as Jacob Boehme found her hidden in Christ's fountain. For the Grail which is the chalice of Christ is also the cup of Sophia. Recognizing the Grail as a symbol of Sophia continues its traditional representation as the feminine dimension of God. The chalice of Christ's blood which symbolizes the presence of God in the physical world points to the Divine Feminine which penetrates all of creation. Thus the Grail represents the spiritual essence of life which infuses nature. This is Sophia as divine immanence, the World- Soul. A major theme of the Grail stories is the loss of this Grail, the loss of the soul of the world, and the devastation of the land which ensues. As Caitlin Matthews points out, the maidens of the wells are the "voices of Sophia in her aspect of World-Soul."(15) Their retreat from the outer world and withdrawal of the nourishing golden cup is symptomatic of our lack of recognition of the soul of the world. When we are once again able to hear Sophia's message through the voices of the well maidens, we will realize that every created thing is seeded with the Divine. When we drink from her cup, we become aware of the sacredness of the natural world.

The paradoxical nature of Sophia's cup is that while it provides limitless nourishment, it is at the same time an empty vessel. For the Grail is the receptive feminine ground from which all nature arises. The mystery of the Grail is that it contains all things and yet it contains no-thing. It contains all of creation within it; but if we gaze long enough into the Grail, following the meditative practice of the mystic, we may see the essential emptiness - the Void which lies before creation and beyond mortality. And when the Void becomes the vessel of our experience in the earthly realm, we experience both the joy and the pain of life. These polarities of existence are expressed in all of the images of the Grail: the cauldron of the Goddess which gives both life and death; the World-Soul which experiences both Wasteland and the Court of Joy; and the chalice of Christ's blood which represents the suffering of Good Friday and the ecstasy of Easter.

The cup of Sophia contains both the light and the dark aspects of existence which arise from the emptiness of the Void, thus symbolizing the wholeness of the Great Goddess. The dark side of the Grail which corresponds to the fear and pain of mortal life refers to the realm of the Black Goddess. Recognizing Sophia in this role helps us to accept the draught from the dark side of the cup of life, realizing the ultimate unity of the light and the dark in Sophia's Grail.

The Grail as chalice of Christ and cup of Sophia represents the union of the masculine and feminine divine images of Christ and Sophia. This unity may be expressed as "ChristoSophia," the differentiated wholeness consisting of a dynamic balance between "Word" and "Wisdom." Instead of disguising Sophia in the figure of Christ as the early Christians did, the term "ChristoSophia" assures that the attributes of both are clearly expressed. Thus the Grail of ChristoSophia reveals the secret of Jesus Christ as the incarnation of Sophia. As the chalice of Christ's blood contains the essence of Christ which is still alive in our world, it conveys the early Christians' understanding of the resurrected Christ's presence in the world as Sophia-Spirit.

Another image of ChristoSophia contained within Grail symbolism can be derived from the statement by Emma Jung that "The Grail really forms a quaternity in which the blood contained within it signifies the Three Persons of one Godhead, and the vessel can be compared to the Mother of God."(16) The Mother of God, while usually designating Mary in Christian terminology, can also be seen as Sophia in her role of archetypal Mother Goddess. In this sense the vessel representing the Divine Feminine is the container for the Trinity. The Grail itself can be compared to Sophia as the ousia, or divine substance, of the Russian Sophiologists. It is in Sophia, as the vessel of the Grail, that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have their Being.

This is the great mystery of the Christian Grail: that the blood of Christ is Sophia's essence of life. The chalice of ChristoSophia is the mystical container for the divine elixir of life. This is the mystery which lies at the heart of Christian tradition: the wine-blood which is received in the Eucharist is Sophia's gift of life - the immortal life of the spirit which is already present in the material world. This is the meaning of Christ's statement in the Gospel of Thomas, "The kingdom of the father is spread out upon the earth, and men do not see it."(17) When we drink from the Grail of ChristoSophia our eyes are opened and we perceive the mystery; then we realize that we already live in this kingdom for we discover that it exists within us and in all

of creation.

Recognizing the Grail as a symbol of ChristoSophia satisfies the need to further develop the Christ symbol by incorporating the natural world and the dark side of the Divine. Christ as the crucified Savior can be associated with the Wounded King who is prominent in many of the Grail stories. The Wounded King symbolizes the image of Christ which is dominant in the collective consciousness, for the repression of the feminine has rendered Christ incomplete and lacking the wholeness of the archetypal divinity. (18) Here the meaning of the King's sickness is that the image of Christ has consequently lost much of its numinous power to attract and transform the soul of the believer. The masculine image of God which has dominated Western culture for the past two millennia is no longer viable in our modern world or in the psyche of modern humans. The new form for the God-image must include the feminine if the wasteland of modern life and spirituality is to be renewed. But since the major theme of the Grail myth is the reuniting of the Goddess and the King, the new myth must be based upon a true synthesis of the masculine and the feminine. The age-old union of the King and the Queen, the Hero and the Goddess, can be translated into Christian tradition in the form of ChristoSophia.

It is the Grail as the symbol of ChristoSophia which will bring healing to the Wounded King by providing the feminine complement that he so desperately needs. This is the Grail which can complete the image of Christ by uniting the world of the feminine, nature, and darkness with the world of the masculine, spirit, and light. It is the Grail which will bring wholeness by uniting the opposites within the Western psyche's image of the Divine. The unfinished nature of the quest in the medieval Grail stories indicates that this quest continues in our time. The quest to bring wholeness to the Christ symbol and the related quest to bring Sophia forth from her hiding places remain unfinished today. Both of these quests, which are really mirror images of the one quest of the Grail stories, have been left for our modern age to complete.

For more information refer to Walking the Path of ChristoSophia: Discovering the Hidden Tradition in Christian Spirituality Chapter X "The Holy Grail"

NOTES

1. Emma Jung and Marie-Louise Von Franz, The Grail Legend (Boston: Sigo Press, 1986), p. 102.

2. Caitlin Matthews, Sophia: Goddess of Wisdom (London: Mandala, 1991), pp. 208-211.

3. Ibid., p. 216.

4. Jung and Von Franz, p. 104.

5. Ibid., p. 315.

6. Ibid., p. 156.

7. Erich Neumann, The Great Mother (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963), p. 326.

8. Joan Engelsman, The Feminine Nature of the Divine (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1979), p. 95.

9. Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza, In Memory of Her (New York: Crossroad, 1992), p. 190.

10. Jacob Boehme, The Way to Christ (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), p. 154.

11. Ibid., p. 45

12. Ibid., p. 10

13. Samuel D. Cioran, Vladimir Soloviev and the Knighthood of the Divine Sophia (Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1979), p. 21.

14. Sergei Bulgakov, Sophia: The Wisdom of God (New York: Lindisfarne Press, 1993), p. 35.

15. Matthews, p. 220.

16. Jung and Von Franz, p. 339.

17. James M. Robinson, ed., "The Gospel of Thomas," The Nag Hammadi Library (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1988), p. 138

Back to top

It is the Grail which can provide the much needed symbol for a revitalized Christian mythos for it integrates the feminine aspect of God with the masculine, thereby including nature and the dark side of existence in its image of the Divine.

A major task of the Gail seeker today who quests for the Grail of Christ is to bring Sophia forth from her hiding places within Christian tradition.

The Grail which is the chalice of Christ is also the cup of Sophia. Recognizing the Grail as a symbol of Sophia continues its traditional representation as the feminine dimension of God

As the chalice of Christ’s blood contains the essence of Christ which is still alive in our world, it conveys the early Christians’ understanding of the resurrected Christ’s presence in the world as Sophia-Spirit.

The chalice of ChristoSophia is the mystical container for the divine elixir of life.